Medical Library

-

Understanding Low Back Pain

Anatomy | Mechanical Low Back Pain | Treating Low Back Pain

It is estimated that 80% of the human race experiences low back pain at least once throughout their lifetime. Fifty percent of the working population admit to experiencing low back pain each year. Each year 15-20% of the people in the United States have complaints of low back pain. Two percent of the U.S. population is either temporarily or chronically disabled by low back pain. Millions of workers suffer on the job injuries annually which costs 100 billion dollars in lost wages, time, and productivity and medical costs.

It is important to understand that there is an outstanding chance that you will recover from your low back pain in the near future. Research studies have shown that 74 % of those that suffer from back pain return to work within 4 weeks and > 90 % in 3 months or less. Some health care providers feel low back pain is like catching a cold - you experience it and in time it goes away.

To sum it up, there is a good chance you will have low back pain, there is a good chance that you will recover but there is also a good chance that you will experience the pain again. Medical research suggests that an active exercise program will reduce disability and may prevent future episodes of pain.

Anatomy of the Low Back

The low back or lumbar spine is an extraordinary engineering marvel. It is composed of bones, discs, joints, tendons, muscles, ligaments and nerves. The spine has 3 main functions. 1.) It connects the pelvis to the trunk and head. 2.) It protects and houses the spinal cord which is made up of billions of nerves that connect the brain to most of the body’s major organs. 3.) The spine provides stability, balance, flexibility, and mobility in order for us to perform our daily activities. It allows you to swing a golf club and at the same time withstands and transfers tremendous forces. For example, let’s assume you weigh 150 pounds, and you bend over about 65 degrees. Your back muscles generate 375 pounds of force to keep you from falling over and if you carry a 50 pound object at the same time, your muscles generate about 700 pounds of force.

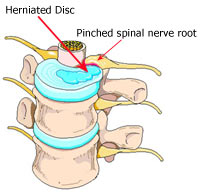

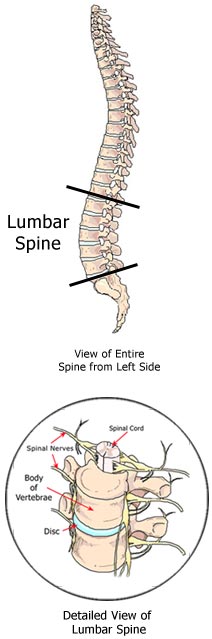

The low back or lumbar spine is an extraordinary engineering marvel. It is composed of bones, discs, joints, tendons, muscles, ligaments and nerves. The spine has 3 main functions. 1.) It connects the pelvis to the trunk and head. 2.) It protects and houses the spinal cord which is made up of billions of nerves that connect the brain to most of the body’s major organs. 3.) The spine provides stability, balance, flexibility, and mobility in order for us to perform our daily activities. It allows you to swing a golf club and at the same time withstands and transfers tremendous forces. For example, let’s assume you weigh 150 pounds, and you bend over about 65 degrees. Your back muscles generate 375 pounds of force to keep you from falling over and if you carry a 50 pound object at the same time, your muscles generate about 700 pounds of force.Closer inspection reveals five vertebrae (bones) stacked on top of each other with a fluid - filled disc in between each vertebrae. The lumbar spine is like a hollow, C-shaped curve (called the lumbar lordosis) which is arranged to balance tremendous forces. The curve or lumbar lordosis allows the spine to be 15 times stronger than if it were straight. Within the "hollow" of the spine is the spinal cord. The spinal cord is made up of nerves that, very simply put, wire your brain to your muscles and tell them when to contract. These nerves also are responsible for the sensation of touch and pain among other things. They exit out of holes called intervertebral (meaning in between the vertebrae) foramen and are called nerve roots.

The vertebral bodies bear most of the weight and have cartilage end plates which attach to the discs. Spinous processes emerge from the back of a vertebrae and two other bones point to the sides and are called transverse processes. These processes serve as attachments for muscles and ligaments.

Between each vertebral body is a fluid filled disc similar to a jelly donut. The outer fibrous portion is called the annulus fibrosus and the inner jelly is called the nucleus pulposus. Healthy discs provide necessary height to the spine, absorb shock, and distribute forces in all directions.

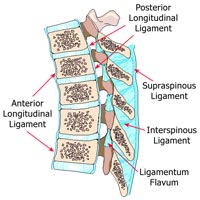

Ligaments are tough non-elastic (they stretch very little) structures that attach a bone or bones together. There are many ligaments associated with the lumbar spine. The anterior longitudinal ligament holds the front of the vertebral bodies together. The posterior longitudinal ligament holds the back of the vertebral bodies together. The interspinous and intertransverse ligaments pass in between the spinous processes and transverse processes respectively. The ligamentum flavum holds the rear portion of the vertebra together and helps to protect the spinal cord. The thoracolumbar fascia is a large piece of ligamentous tissue that helps hold all of the lumbar vertebra together and works with muscles to stabilize the spine.

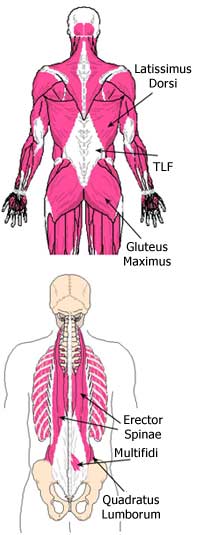

Ligaments are tough non-elastic (they stretch very little) structures that attach a bone or bones together. There are many ligaments associated with the lumbar spine. The anterior longitudinal ligament holds the front of the vertebral bodies together. The posterior longitudinal ligament holds the back of the vertebral bodies together. The interspinous and intertransverse ligaments pass in between the spinous processes and transverse processes respectively. The ligamentum flavum holds the rear portion of the vertebra together and helps to protect the spinal cord. The thoracolumbar fascia is a large piece of ligamentous tissue that helps hold all of the lumbar vertebra together and works with muscles to stabilize the spine.There are over 140 muscles that work together to move and stabilize the spine. Many of these muscles are located around the lumbar spine. There are the abdominal muscles, the erector muscles, the hip muscles, and lateral stabilizing muscles. The abdominal muscles consist of the rectus abdominus, the internal and external obliques, and the transverse abdominus. They provide frontal support, help maintain good posture, hold the abdominal organs in the correct location, and act together as your body’s own natural "back belt." The erector spinae muscles run up and down your back to help you maintain erect posture and they assist in recovering from the forward bent position. Even deeper is a layer of muscles that assist in rotational movements and side bending. The hip muscles, most notably the gluteus maximus, hamstrings, and psoas (pronounced soas) move the pelvis and thighs. The gluteus maximus and hamstrings are your major lifting muscles. In fact, when you bend down to touch your toes, about 67% of the bending comes from your hips which is in turn controled by the gluteus maximus and hamstrings muscles. The psoas muscles help lift your thigh and stabilizes the spine. The lateral stabilizers - the quadratus lumborum and the latissamus dorsi both insert into the spinous and transverse processes via the thoracolumbar fascia. They also stabilize and move the spine. Any one or combination of structures can affect the curve or lumbar lordosis.

Mechanical low back pain has been reported to arise from trauma (either chronic or sudden) such as a fall, a motor vehicle accident, twisting, prolonged poor postures, mental stress, fatigue, disc extrusion (also known as a slipped disc, rupture, or disc herniation), sometimes painful degenerative disc disease(also called arthritis), aging, congenital defects, poor flexibility, etc. Causes such as infection, hormonal problems, broken bones, systemic disease, and tumors require serious medical intervention but are very rare and are beyond the realm of this discussion.

Acute low back pain is defined as activity intolerance due to lower back or back-related leg symptoms of less than 3 months' duration. Chronic low back pain, therefore, is defined as pain/problems lasting greater than 3 months. Regardless of the cause or duration of mechanical low back pain, the result is likely to be damaged soft tissue(s) which can stimulate nerves and produce pain.

It is important to understand that it is next to impossible to determine exactly which tissue(s) are the cause of the low back pain. Someone like yourself may be experiencing pain and quite frankly, the cause is unknown. It could be muscle(s), ligament(s), disc(s), tendon(s), joint(s), and/or other connective tissue. They all can produce similar symptoms which commonly present as pain on one side of the back or across the back. It may radiate into the buttock or into the thigh. Quite often it will be accompanied by painful cramping of the muscles called a muscle spasm. Furthermore, medical research has shown that x-rays are of little help in determining the cause of low back pain except in rare cases such as severe trauma. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also ineffective at determining the cause of low back pain. For example 2 out of 3 people have positive findings for disc abnormalities on an MRI but are painless. As many as 1 in 3 people have disc bulges and are completely painless. Health care professionals often call low back pain a "pain in search of a pathology." This means that a patient’s medical tests will be negative or a test will produce a false positive. The cause could be any number of structures.

Treating Low Back Pain

So how do we treat something if we don't know what exactly is wrong. We do know that mechanical low back pain is caused by damaged soft tissue. The damage stimulates pain nerves called nociceptors. The goal then is to promote healing of the damaged soft tissue which will eliminate the pain, not just treat the pain itself. This is done with a program that is customized to your individual needs.

So how do we treat something if we don't know what exactly is wrong. We do know that mechanical low back pain is caused by damaged soft tissue. The damage stimulates pain nerves called nociceptors. The goal then is to promote healing of the damaged soft tissue which will eliminate the pain, not just treat the pain itself. This is done with a program that is customized to your individual needs.Here are the steps:

- Protecting the damaged soft tissue to prevent further breakdown. The area of damaged soft tissue is protected with rest and positioning. Activities that cause the pain should be avoided while the low back heals. Pain management techniques should be used and your physical therapist will discuss these with you. Bed rest is usually only necessary for 1-3 days (longer periods of bed rest have not been proven to be beneficial).

- Increasing the circulation and mobility. This will deliver the proper building blocks (proteins, repair cells called fibroblasts, oxygen, proteins, etc.), remove inflammatory and waste products that build up in painful tissue(s), and prevent tissue atrophy. Increasing circulation is accomplished by walking and performing painless range of motion, stretching, and strengthening exercises.

- Correcting the dysfunctions (weakness, poor posture, poor flexibility) that caused the problem in the first place. Progressive strengthening exercises, flexibility exercise, and postural/body mechanics education will help reduce the stress on your low back and promote proper repair.

The Key: Your physical therapist will give you the tools to treat your dysfunctions and create your own customized treatment program. That's not all. Anyone who has suffered from low back pain must understand that the problem is not corrected when the pain ends. Muscles must be stronger than before the pain started (that takes 12+ weeks), many weeks are needed to improve flexibility, and repeated practice is necessary to incorporate proper posture and body mechanics into your daily activities.

-

Possible Treatments

-

Aerobic/Endurance Exercise

Video

-

Core Strengthening

Video

-

Cryotherapy or Cold Therapy

Video

- Electrotherapeutic Modalities

-

Gait or Walking Training

Video

-

Heat Pack

Video

-

Isometric Exercise

Video

-

Low Back Active Range of Motion

Video

-

Low Back Joint Mobilization

Video

-

Low Back Passive Range of Motion

Video

-

Low Back Resistive Range of Motion

Video

-

Lumbar Traction

Video

-

McKenzie Exercise

Video

-

Posture Training

Video

-

Proprioception Exercises

Video

- Physical Agents

-

Soft Tissue Mobilization

Video

-

Stretching/Flexibility Exercise

Video

-

Aerobic/Endurance Exercise

-

Possible Treatment Goals

- Decrease Risk of Reoccurrence

- Improve Fitness

- Improve Function

- Improve Muscle Strength and Power

- Increase Oxygen to Tissues

- Improve Proprioception

- Improve Range of Motion

- Improve Relaxation

- Self-care of Symptoms

- Improve Safety

- Improve Tolerance for Prolonged Activities

-

Additional Resources

- 3d Anatomy of one low back and pelvis

- 3d Anatomy of one lower back and spine

- Ankylosing Spondylitis

- Acute Low Back Pain Who Will Respond to Treatment

- Back Pain in Children

- Back Pain from Medline Plus

- About Rheumatoid Arthritis from the Arthritis Foundation

- Rheumatoid Arthritis Resources

Back Articles

Pick a Body Area

Other Choices

Systemic Treatments Exercises For Physicians NewslettersDisclaimer

The information in this medical library is intended for informational and educational purposes only and in no way should be taken to be the provision or practice of physical therapy, medical, or professional healthcare advice or services. The information should not be considered complete or exhaustive and should not be used for diagnostic or treatment purposes without first consulting with your physical therapist, occupational therapist, physician or other healthcare provider. The owners of this website accept no responsibility for the misuse of information contained within this website.